How this survivor stopped worrying and learnt how to love the great white shark

Author: Sue Williams Source: www.smh.com.au Website: Visit Website Date:Sunday, 8 December 2013

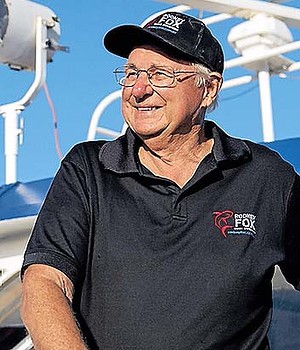

His death-defying story has been told often in the past 50 years, but Rodney Fox's focus is the plight of the ocean's great predator.

Clamped between the jaws of a massive shark and being dragged further and further underwater, life-insurance salesman Rodney Fox could think of only one thing to do: claw madly at its eyes.

Surprised, the shark dropped him. Fox was even more surprised, as he felt his body graze across the razor-sharp teeth and he suddenly fell free. He thrashed towards the surface but, as he looked down through the blood-red water, all he could see was a wide-open mouth coming back up for him.

But then, he says, ''a miracle happened''. The shark went instead for the bright-yellow buoy Fox had been towing as he took part in a spearfishing championship off the South Australian coast. As the shark dived into the depths, Fox was yanked with it for a moment, and felt that death would surely come soon, until the rope snapped.

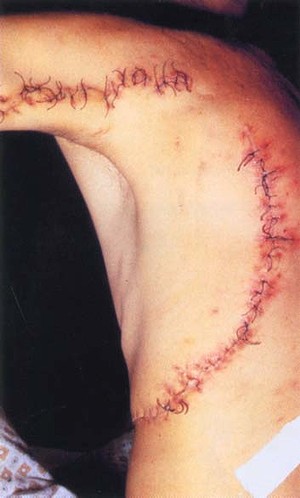

Stitched up: Rodney Fox's stiched torso after the near-fatal attack 50 years ago.

Fox today.

It's an attack, 50 years ago today, that has earned a place in the annals of world shark history as one of the worst non-fatal shark attacks of all time, leaving Fox, now 73, as the one who got away.

Of course, he didn't make it wholly intact - it took many months of surgery and 462 stitches to repair the huge gashes in his chest and shoulder, and for his punctured lung and every broken rib to heal. And it took years for the tooth left embedded in his right wrist to dissolve to now just a small bump under the skin.

Even more astounding than the then 23-year-old's survival is his transformation from a man not terribly fond of sharks to one of their greatest fans and champions.

''Of course, I wasn't very happy with the shark that did that to me, but I didn't hate all of them as a result,'' he says.

Today he takes tourists, expeditions and film crews in a boat off South Australia's Port Lincoln to view great white sharks through the bars of an underwater cage that he invented.

''You might be involved in a car crash, but that doesn't mean you'd hate all cars.

''Sharks are magnificent creatures and there are a lot fewer of them around now because so many have been killed over the years, either deliberately or caught in nets, and they take a long time to breed and mature.

''Today, they're one of the most feared predators, but I don't understand why. Consistently, they've caused six to eight deaths around the world a year, but that's nothing compared with the number of deaths from, say, drowning.''

In the past 50 years in Australia, according to the Australian Shark Attack File kept by Sydney's Taronga Zoo, there have been only 50 unprovoked fatalities from shark attacks, compared with an average of 121 deaths every year from people drowning. But people do love to be thrilled by the unknown, as well as hearing those great survival tales of man versus shark, and don't forget the 1975 movie Jaws.

At mention of the film, Fox looks abashed. He bears some responsibility for demonising the great whites. He was hired by director Steven Spielberg to take a cameraman out to film them, with the footage to be intercut with scenes of fake mechanical sharks.

Even worse, he was supplied with a 1.4-metre tall stuntman, who usually doubled for children, and a half-size cage to make the sharks he found look even bigger.

''None of us knew that the film would turn out to be such a hit,'' he says, almost apologetically. ''Even today, people tell me they're terrified of sharks because of that film. But it was fiction. Sharks don't actually plot to kill humans, but that had a big effect on people's psyche. I'm not proud of my role in that.''

Today, Fox is renowned for his work to turn great whites - the world's largest known underwater predator at up to six metres long and weighing up to three tonnes - into a protected species. The area to which he takes visitors to view the creatures, by the Southern Ocean's Neptune Islands, 70 kilometres south of Port Lincoln, is a conservation park.

''He was a pioneer of the conservation of sharks before it was cool,'' says his eldest son, Andrew, 48, now working with him in the business, Rodney Fox Shark Expeditions. ''I heard dad's story hundreds of times when I was growing up, and I caught the shark bug early. I now share his passion. It's like being born into the royal family of sharks. I have to keep the legacy going.''

These days, Andrew's in charge of much of the scientific research the company undertakes, including satellite tagging of the sharks. The pair have got to know many of them too. Particular favourites include Chompy, who looks like he's smiling when he glares at humans, Mad Max, a particularly unpredictable male, ET, named for his misshapen dorsal fin, and Scarface.

Since the attack, sharks have been good to Fox. In the early days, he did very well selling life insurance, as the perfect advertisement and the man everyone wanted to talk to, even if it meant feeling obliged to buy a policy from him in return.

A stint as an opal miner proved less profitable, but running the shark trips has been extremely successful.

Yet while the creature at the top of the underwater food chain spectacularly didn't get Fox, bizarrely one close to the bottom did. He has recently developed a severe allergy to prawns.

''I'm a glass-half-full kind of person,'' Fox says. ''I don't remember the pain and the bad times. I just think what beautiful creatures sharks are and how fortunate I was to be in a shark's mouth and to get out of it alive. There's not many who can say that.''